Now 54 years old, Ferguson was diagnosed with clinical depression when he was 18. Since then, he estimates, he’s been prescribed more than a dozen medications — SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants — all to little or no avail.

“I never got to the point that I thought, ‘OK, I’m feeling good,’ ” he said. “It was always, ‘OK, this is tolerable.’ But yet those thoughts [of wanting to die] were still there.”

In early May, Ferguson abruptly stopped taking all of his medications, quit his job and gave away his dog, Zeke. That evening, he called his sister, Linda.

“It was a very good conversation,” he said. “Lindaand I disagree on a lot of stuff, and that night I avoided the hot-button topics because I did not want her to have bad memories or bad thoughts of what I thought was going to end up being our last conversation.”

As luck or fate or professional intuition would have it, on a prescheduled call the very next day, Ferguson’s psychiatrist offered to refer him to a ketamine clinic in Milwaukee, about an hour and a half from his home.

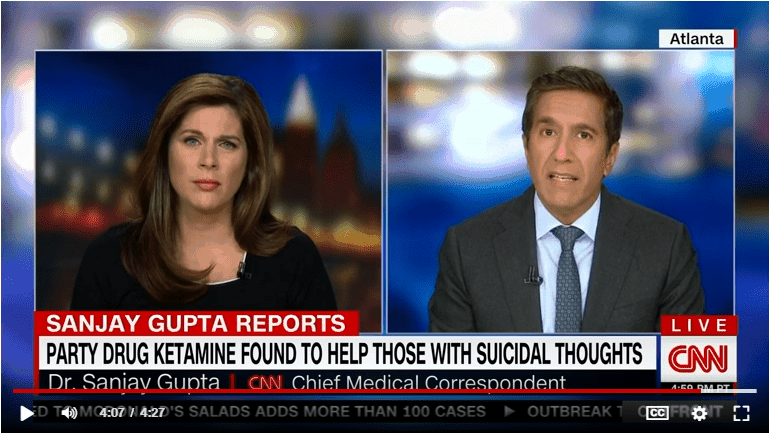

Ketamine is a powerful medication used in hospitals primarily as an anesthetic, but

recent scientific studies have shown significant promise with treatment-resistant depression and suicidal ideation.

Ketamine is also used recreationally, and illegally, as a club drug known as “Special K.” It generates an intense high and dissociative effects.

“I knew of the drug from having been a police officer, so I knew of its street use — illicit use — but I’m a pretty open-minded person too, and after all the traditional medications I’ve been on with no success, I thought, ‘Well, maybe they’re on to something here with this,’ ” Ferguson said. “I wasn’t worried about trying something I had never tried before. I was worried about trying something else that wasn’t going to work.”

A last hope

Ferguson put off his plans to end his life for another week and made his way to

Ketamine Milwaukee. The clinic operates once a week, on Fridays, in a space subleased from a weight-loss clinic in a nondescript strip mall just outside the city.

Dr. Kevin Kane, a practicing anesthesiologist, is Ketamine Milwaukee’s medical director. Referring to the fact that there haven’t been any new classes of drugs developed to treat depression in decades, Kane said that using ketamine to successfully treat the disorder’s most stubborn cases might just be “the biggest breakthrough in mental health in the last 50 years.” He estimates that it is effective for 70% of patients with treatment-resistant depression.

“It’s indicated right now for … somebody who has tried and failed at least two medications, but that’s really not who we’re seeing,” Kane said. Instead, the patients who seek his care have tried more medications than they can count. Some of them have been depressed for as long as they can remember.

“The people we’re seeing aren’t walking off the street because [they’re] feeling a little down,” he said. “They’ve been struggling without relief for a long time.”

The ketamine is administered intravenously, and relief can come quickly — in just a matter of hours.

Ferguson said he woke up the next morning anxiously anticipating his pervasive “I need to be dead” thoughts. But there were none. Mid-morning: still none. Afternoon: none. Evening: none.

“No negative thoughts!” he recalled. “My problems still existed … but things were different. My most faithful, lifelong companion was gone!”

Ferguson doesn’t like to use what he calls the “m-word”: miracle. But he will refer to the way in which ketamine worked for him a medical marvel.

Whatever you call it, the treatment doesn’t come cheap. Infusions at Ketamine Milwaukee cost $495 each, and Kane typically recommends an initial series of five to six infusions, after which patients generally return every four to six weeks for booster infusions.

Because treating depression with ketamine is an “off-label” use of the drug, it is not covered by health insurance, even when it is recommended by a doctor. Ferguson was able to scrape together enough cash for his first infusion. A good friend gave him the money for his second. And his church rallied around him and paid for his third treatment. But the results, he will tell you, are priceless.

No more suicidal thoughts

Because of how quickly and how well ketamine works in some patients, some doctors have referred to it as a “save shot” for people who are suicidal.

“The ketamine may be a way to improve their mood and stop their suicidal thinking until the other antidepressants — the more standard antidepressants — have the six-week time window to work,” Kane said. “Ketamine may be just the thing that gets someone through that window until other medications get the chance to kick in.

“Sometimes, when you get so depressed that you can barely get out of bed, it’s hard to do the things that your therapist tells you to do to try and help yourself,” he said. “My hope is … that it gives people that lift in mood that allows them to start doing the other things that they know they can do to help themselves.”

Kane explained that ketamine works in depressed patients by growing synapses in areas of the brain that have atrophied, namely the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. “If you think of it like a tree that loses its leaves in wintertime, ketamine helps grow those leaves back,” he said. “It doesn’t necessarily have to grow an entire new branch or an entire new tree. It just has to sprout new leaves.”

Moreover, the same dissociative properties that made ketamine a popular party drug are what makes the medication so effective in treating severe depression.

“Sometimes, that can be a very powerful thing, that dissociation,” Kane said. “While you’re dissociating from your body, you may be dissociating [from] your mind as well. And, you may be able to see your problems and your issues that have really been consuming you as, ‘Yes, they’re still here, but now they’re over there. They’re in a little ball in the corner, and they don’t have the power over me anymore.’

“Sometimes, people can have very profound thoughts along those lines and realizations that they can take back to their therapy session, and [it] can be a really wonderful stepping stone for them to help maintain their relief.”

Dr. Gerard Sanacora, a psychiatry professor at the Yale School of Medicine, said little to no doubt remains about the rapid, robust anti-suicidal effect of ketamine. “I think the bigger question is: How do you maintain this? And how do you decide who is the best patient to receive this?”

Clinical studies have established that immediate side effects of ketamine can include increased heart rate and blood pressure. But Sanacora said further research is needed to determine the long-term cognitive impacts of ketamine treatment, as well as to develop standard dosing guidelines.

Sanacora, who is a co-author of “

A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders,” published in the medical journal JAMA Psychiatry, said that “for the majority of people — not everybody — symptoms do tend to return after some period of time.”

At least as of now, more than two months since beginning ketamine therapy, Ferguson said he hasn’t had a single thought of taking his own life.

“It really is remarkable for me to be able to wake up and not be sorry I woke up in the morning,” he said. Still, Ferguson is keenly aware that the drug is not a miracle cure, and he will require ongoing care for the rest of his life.

After receiving a ketamine infusion in June, Ferguson thanked Kane not just for saving his life but for giving him a life he never knew was possible.